Sporanox

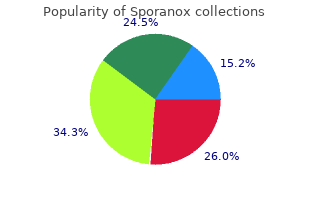

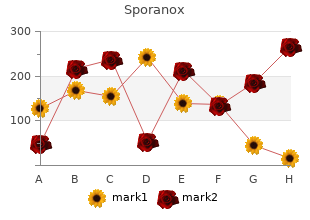

"Purchase sporanox 100mg on line, african violet fungus gnats."

By: Stephen Joseph Balevic, MD

- Assistant Professor of Pediatrics

- Assistant Professor of Medicine

- Member of the Duke Clinical Research Institute

https://medicine.duke.edu/faculty/stephen-joseph-balevic-md

A token of this lies in the formulation by the German psychiatrist Emil Kraepelin of dementia praecox (liter ally anti fungal supplements cheap sporanox 100 mg without prescription, precocious dementia) pyrithione zinc antifungal buy sporanox 100 mg with visa, shortly to fungus gnat damage purchase sporanox on line amex be termed schizophrenia by the Swiss doc tor, Eugen Bleuler. As depicted by Kraepelin in Einfurung die Psychiatrische Klinik 300 The Cam bridge Illustrated H istory oe M edicine (Lectures in Clinical Psychiatry) in 1901, the archetypal schizophrenic was not stupid; on the contrary, he might be alarmingly intelligent and astute. Yet he seemed to have renounced his humanity, abandoned all desire to participate in human society, withdrawing into an autistic world of his own. Describing schizo phrenics, Kraepelin used such phrases as ‘atrophy of the emotions’ and ‘vitiation of the will’ to convey his conviction that such patients were moral perverts, sociopaths almost a species apart. The more lurid fantasies of degenerationist psychiatry its egregious racism, hereditarianism, and sexual prurience were denounced by Sigmund Freud and other champions of the new dynamic psychiatries arising around the beginning of the twentieth century. And the therapeutic innovation at the heart of psycho analysis proposed yet another optimistic new deal: the talking cure. Specially significant has been the grand differentiation between psychoses (severe disturbances, involving loss of contact with reality) and neuroses (relatively mild conditions). That has been popularly seen as the grounding for distinctions between conditions with real organic aetiologies and ones that are psychological. Among the psychoses, a fur ther cardinal contrast has been established between manic-depressive (or bipolar) conditions and schizophrenia. Nevertheless, delineation and classification of mental illnesses remains fiercely contested. A notorious postal-vote poll, held by the American Psychiatric Associa tion in 1975, led to homosexuality being belatedly removed from its list of mental afflictions. It is not only cynics who claim that politico-cultural, racial, and gen der prejudices continue to shape diagnoses of what are purportedly objective dis ease conditions. Psychopharmacology had long been burdened with worthless weapons such as bromides and croton oil (a powerful purge that put the patient out of action). From the 1950s, neuroleptics such as chlorpromazine (Largactil), used on schizophrenics, and lithium, for manic-depressive conditions, had remarkable success in stabilizing behaviour. They made it possible for patients to leave the sheltered but numbing environment of the psychiatric hospital. Mental Illness 301 Quick-fix procedures the failure of the nineteenth-century asylum to fulfil its Also in the 1930s, lobotomy was developed by the Por promise led to a renewal of more direct medical interven tuguese physician, Antonio Egas Moniz, and popularized by tions, not least a succession of high-tech, quick-fix, proce the American neurologist, Walter Freeman. First used by an Italian, Ugo Cerletti, in 1938 it is still occasionally used today. Here Cerletti describes the strain of the first experiments with it: Two large electrodes were applied to the frontoparietal regions, and I decided to start cautiously with a low intensity current of 80 volts for 0. As soon as the current was introduced, the patient reacted with a jolt and his body muscles stiffened; then he fell back on the bed without loss of consciousness. Naturally, we, who were conducting the experiment were under great emotional strain and felt that we had already taken quite a risk. Nevertheless, it was quite evi dent to all of us that we should allow the patient to have some rest and repeat the experiment the next day. I confess that such explicit admonition under such circumstances, and so emphatic and commanding, com ing from a person whose enigmatic jargon had until then been very difficult to understand, shook my deter mination to carry on with the experiment. But it was just this fear of yielding to a superstitious notion that caused me to make up my mind. The electrodes were A paralytic mental patient having his blood sampled at the applied again, and a 110-volt discharge was applied for Vienna Psychiatric Clinic, under the direction of Julius 7 0. An ex-patient, Jimmie Laing, described the ‘Largactil kick’: ‘You would see a group of men sitting in a room and all of them would be kicking their feet up involuntarily’. A genera tion ago, the British pyschiatrist William Sargant and other leading members of the profession prophesied that wonder drugs like Largactil would render mental illness a thing of the past by 1990. As early as mid-Victorian times, when the asylum-building programme was still in its infancy, even psychiatrists were prepared to admit that a gigantic asylum was a gigantic evil. A full century before the modern antipsy chiatry movement, the Victorians had seen the untoward effects of institutional ization.

Syndromes

- Infants in a nursery where an outbreak has occurred

- Vomiting

- Spinal cord injury

- Breathing problems

- Apert syndrome

- Difficulty breathing

- Thiothixene (Navane)

- Osteomyelitis (bone infection)

- Rash

- Police department police

In the third book – devoted to fungus removal order sporanox mastercard ‘hearing fungus under fingernails sporanox 100 mg lowest price,’ a sense that imparts reasoning but is potentially deceptive – the two principals engage the more skilled artisans and a Captain fungus hives cheap 100mg sporanox amex, while the fourth book’s devotion to ‘smell’, also a potentially unreliable sense, portrays an actress proclaiming her revulsion at death and defending the practice of her craft. In the fifth book and its devotion to ‘touch’, the least deceptive sense, the philosopher and courtier speak with a well-educated man on his deathbed, seeing him through to a 92 tranquil end. Indeed, the fact that ‘he always worked, and never missed the opportunity to work’ was an observation made about the young Giambattista by his contemporary Pietro Malta, and corroborated by three other witnesses in the case brought against Giambattista by members of his late 93 brother’s family in February 1750. Giambattista’s absolute commitment to work, combined with an exhaustive lifetime of commissions to the last, may have been a contributory factor to the painter’s sudden, unshriven and unannointed, end. The mors repentina, mors improvisa, or unexpected death which came before confession and 94 the forgiveness of sin was greatly feared in the early modern period, hence the central message of Glissenti’s text is that fathers should teach their children the art of living and dying as they teach their children a trade. In view of the fact that Giambattista died without the benefit of the last sacraments, it would seem reasonable to deduce that, for Domenico, the very notion of dying was closely bound up with his father, the father who also taught him a trade. The desire to preserve memory in terms of monuments and objects of commemoration can be a natural response following the death of relatives or admired individuals. Such a desire, it seems, was acutely felt by Domenico following Giambattista’s death in 1770. This is reflected by the fact that Domenico made a commemorative etching of Giambattista’s last public commission, the painting showing San Pascual Baylon for the church dedicated to the saint on the outskirts of Aranjuez, underneath which he added the following telling inscription: ‘Giambattista 93 “Io so che ha auto sempre da lavorare e mai gli è mancato il lavoro. When Domenico returned to Venice from Spain, one of his priorities was patently to commemorate his father. He did this by publishing four editions of the family etchings between 1774 and 1778; these were mostly of Giambattista’s masterpieces, alongside etchings by Lorenzo and himself. Similarly, the Scherzi di Fantasia, a series of twenty-three prints made by Giambattista, which had not been circulated during the artist’s lifetime, was widely disseminated by Domenico in a number of editions. Significantly, Domenico annotated his father’s frontispiece in order to commemorate Giambattista: thus, the originally blank stone tablet, surmounted with owls, was subsequently inscribed by Domenico to read: ‘Scherzi di Fantasia, from the celebrated Signor Gio. Batta Tiepolo, Venetian Painter, [who] died in Madrid in the Service of King Charles of Spain. Additionally, as I have already argued, in view of his father’s spiritually inconclusive end, he was also concerned with ordering his own affairs in preparation for his eventual demise and, taking into account, his artistic heritage there was also the question of how, as an artist, he could approach old age in a dignified manner. If Tiepolo senior followed a tradition established by some of the great artists of the 95 Joan Bapta. Fritz, ‘The Trade in death: the Royal Funerals in England, 1685-1830,’ in Eighteenth-Century Studies, 15, no. Certainly the pedagogical route, suggested by Borghini, was one that he 97 observed first by becoming a maestro at the Venetian Academy in 1772, where he 98 was eventually elected President in 1780. In the light of the fact that he had chosen a selection of his father’s drawings and etchings for posthumous publication, perhaps Domenico’s drawings were to become his own memorial. Possibly the large biblical drawings celebrated his faith and that aspect of his work which had been concerned with religious themes, the scenes of contemporary life commemorated the people and the city in which in had grown up, flourished and lived most of his life, and the broad themes that Domenico addresses in the Divertimento are the themes of life itself. Occasionally Domenico refers to specific aspects of eighteenth-century Venetian life such as villeggiatura and carnevale, and even self-referentially to familiar themes and facets of his own working life as an artist. Towards the end of Remembrance of Things Past, Marcel Proust undergoes an epiphany when it dawns on him that all the material for his work of art could be drawn from his own past experiences: ‘And then a new light, less dazzling, no doubt, than that other illumination which had made me perceive that the work of art was the sole means of rediscovering Lost Time, shone suddently within me. And I understood that all these materials for a work of literature were simply my past life; I understood that they had come to me, in frivolous pleasures, in indolence, in tenderness, in unhappiness, and that I had stored them up without divining the purpose for which they were destined or even their 97 Tiozzo (2003), p. Scott Moncrieff, Terence Kilmartin and Andreas Mayor, (London: Chatto & Windus, 1981), pp. The sequences which form Pulcinella’s life, more often than not, amount to episodic meditations about art, and many familiar motifs from Domenico’s world which were connected with it. It is as though advancing age might lend itself to reflection of this sort about one’s art, whether it be writing, sculpture, painting, or musical composition, and to using the same medium – in Domenico’s case, drawing – to articulate these reflections. In this sense, Divertimento per li Regazzi represents an important, albeit unusual, art-historical case-study which offers an opportunity for exploring how one artist responded to the onset of old age, the extinction of his family line, and the prospect of his own mortality, as well as the end of a cultural and political tradition. Whilst there is some textual, pictorial and circumstantial evidence to construct an account of Domenico’s reasons for making a pictorially complex series such as the Divertimento in his, the hypotheses explored in this narrative must ultimately be framed in the subjunctive. This thesis began by exploring Domenico’s roots and the fact that he was born into a Venetian artistic dynasty established by his ambitious father. He was raised, to borrow the words of his contemporary, Alessandro Longhi, to be his father’s ‘most diligent imitator’, and primarily practiced as a history painter in Giambattista’s workshop, notwithstanding a personal predilection for painting scenes of contemporary Venetian life. His well-respected father undoubtedly eased Domenico’s debut into local artistic circles, and leading figures in the Venetian art world of the eighteenth century, most notably Anton Maria Zanetti the Elder and Count Francesco 202 Algarotti, in turn, gave him entrés with important connoisseurs and patrons throughout Europe.

Relevance of intraocular involvement in signifcantly improves outcome in primary cns lymphoma: the frst randomization the management of primary central nervous system lymphomas fungus vs eczema purchase sporanox 100mg with amex. Cancer has become a major killer in the world which almost surpasses the cardiovascular diseases and will become the main lethal 5 fungal wart discount 100 mg sporanox overnight delivery. Besides that there are so many types of serious side efects caused by the tumor itself be it solid cancer or hematological cancer fungus covered chest nagrand 100mg sporanox sale. Terefore it became an obligate matter for all clinicians the cancer patients who receive chemotherapy in order to prevent to be aware of these chemotherapy side efects. Moreover it is important to focus on research within this feld in order to detect the Chemotherapy Background proper ways which can help to overcome these side efects. Chemotherapy was developed and used since the Word War I References from the chemical weapon program of the United State of America 1. In thackery, (edn) the gale potentially high risk with many side efects which are difcult to encyclopedia of cancer detroit, gale group. The goal of chemotherapy is to be as efective as possible with tolerable side efects, since the dose of chemotherapy will be toxic to the cancer cells as well as to the normal cells. A proportion of the cancer patients sufer from only mild side efects whereas others may sufer from serious side efects. Occurrence of specifc side efects will vary according to the chemotherapy or medications used. The most common side efects experienced are nausea and vomiting, anemia, hair loss, bleeding (thrombocytopenia), hyperuricemia, bone marrow depression, alopecia and mucositis. So diferent parameters must be taken into consideration to prevent, reduce and overcome these side efects [3-5]. Classifcations of Chemotherapy Side Efects *Corresponding author: Bassam Abdul Rasool Hassan, Clinical Pharmacy Discipline, School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Sains Malaysia, 11800, The side efects commonly associated with chemotherapy treatment Minden, Penang, Malaysia, Tel: +6-016-423-0950; E-mail:bassamsunny@yahoo. This risk is conditioned by a range of factors, including the high cell turnover rate of the oral mucosa, the diversity and complexity of the oral microfora, and soft tissue trauma during normal oral function. The present study offers a literature review of the main oral complications secondary to chemotherapy, and describes the different options for dental treatment before, during and after oncological treatment, published in the scientifc literature. To this effect a PubMed-Medline search was made using the following keywords: chemotherapy, can cer therapy, dental management, oral mucositis, neurotoxicity, intravenous bisphosphonates and jaw osteonecrosis. The search was limited to human studies published in the last 10 years in English or Spanish. A total of 50 articles were identifed: 17 research papers, 25 reviews, 6 letters to the Editor, and two clinical guides developed by expert committees. The data obtained showed the main oral complications of chemotherapy to be mucositis, neurotoxici ty, susceptibility to infections, dental, salivary and taste alterations, and the development of osteonecrosis. Based on the reviewed literature, elective dental treatment can be provided before chemotherapy, with emphasis on the elimination of infectious foci. During chemotherapy, dental treatment should be limited to emergency procedures, while dental treatment of any kind can be prescribed after chemotherapy – with special considerations in the case of patients who have received treatment with intravenous bisphosphonates. Key words: Chemotherapy, cancer treatment, dental treatment, oral mucositis, neurotoxicity, jaw osteonecrosis, intravenous bisphosphonates. Introduction most commonly used in head and neck malignancies are Anticancer chemotherapy currently involves the use of bleomycin, cisplatin, methotrexate, 5-fuorouracil, vin drugs (cytostatic or cytotoxic agents) that avoid prolife blastine and cyclophosphamide (2). The main problem posed by such Antineoplastic drugs can act upon the different tissues ei treatment is the lack of selectivity of most antineoplastic ther directly or indirectly. The direct side effects of such drug substances, since they also act upon normal cells drugs start with the primary oral tissue damage caused with an accelerated cell cycle, such as bone marrow by their indiscriminate effect upon the cell replication cells, hair follicle cells and the epithelial cells of the cycle, such as for example in the oral mucosa, where gastrointestinal tract (1). Dental abnormalities in children after chemotherapy treatment for acute lymphoid Minicucci et al. Sepúlveda Oral ulcers in children under chemotherapy: clinical characteristics and their relation with Med Oral Patol Cross 2005 et al. López-Galindo Clinical evaluation of dental and periodontal status in a group of oncological patients Med Oral Patol 2006 Case-control et al. J Oral Oral bisphosphonate-induced osteonecrosis: risk factors, prediction of risk using serum Marx et al. The Impact of low power laser in the treatment of conditioning-induced oral mucositis: A Med Oral Patol Antunes et al.

The operation fungi definition science purchase 100mg sporanox with visa, first undertaken at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore in 1944 (see page 8) antifungal ointment best 100 mg sporanox, launched modern cardiac surgery fungus body wash buy sporanox 100mg without prescription. The pioneer was Helen Brooke Taussig, an American paediatrician who was the first woman to become a full professor at Johns Hopkins University. Taus sig worked on congenital heart disease in association with the cardiac surgeon Alfred Blalock. The babies were blue because of congenital anomalies that caused blood to pass directly from the right chamber of the heart to the left without being oxygenated in the lungs; this was then surgically rectified. Operations on the mitral valves increased, but in some cases they initially pro duced severe brain damage by depriving the brain of oxygen. The idea was then floated of entirely removing the heart from the body, and deploying an alternative system of blood circulation. In iron lungs, artificial ventilation is maintained for long periods of time by applying alternating negative and positive pressure to the inside of a rigid metal tank, within which the patient’s body, excluding the head, is enclosed. It was developed by an American public health engineer, Philip Drinker, in the 1930s. One was the use of hypothermia, reducing through cold the oxygen need of the tissues. Another was the building of the heart-lung machine, maintaining artificial circulation through the great vessels while the heart was bypassed and the operation performed. The machine involved two main components: a ‘lung’ to oxygenate the blood and a ‘heart’ pump. Through experi ence it was discovered that the deeply cooled and bypassed heart could be stopped for up to an hour and started again without suffering damage. Successful skin grafts were described by the Swiss, Jacques Reverdin, as early as 1869. Such autografts (tissue transplantations within the same patient) were soon used to treat ulcers and burns. Skin grafting led to the rise of reconstructive surgery, first 238 The Cam bridge Illustrated H istory of M edicine through the work of Harold Gillies on First World War casualties at Aldershot in southern England. During the Second World War, transplantation of non-vital tis sue become urgent, to provide ‘pacemaker’ support for regeneration of connective tissues after severe injuries. The invention of the ‘artificial kidney’ laid the foun dations for the great developments in organ transplantation in the 1950s and 1960s. The rise of organ transplantation brought inescapable ethical and legal predica ments for medicine. Under what circumstances might living human beings ethi cally become donors of kidneys and other organs? Were the dead automatically to be assumed to have consented to the removal of organs? Partly in view of the demands of transplantation, the general test of death has shifted during the last generation from cessation of breathing to ‘brain death’, which has the convenience of permitting removal of organs from patients in whom respiration was artificially maintained right up to removal. They became properly feasi ble with the discovery of blood groups early in the twentieth century. It was only during the 1930s that the principles and practi calities of blood storage were worked out, allowing the development of national blood transfusion services and the vast quantities of blood required for certain modern operations. The device, made of aluminium, wood, and Cellophane, was to serve as a model for the kidney machines used throughout the world today. The artificial kidney allowed damaged kidneys time to recover and chronic renal failure to be counterbalanced over a long period. A series of Cellophane membranes remove impurities from the blood that would ordinarily be filtered out by the healthy kidneys. Among Kolffs later achievements were a heart-lung machine and an early artificial heart. The transplant of organs, however, required a solution of the problem of rejection, a subject highlighted by the inves tigations of Frank Macfarlane Burnet in Australia and Peter Medawar in England into the tendency of the immune sys tem to reject grafts. Around 1960, the first immunosuppressant drugs were introduced notably, corti sone, azaserine, and azathioprine. By blocking the produc tion of antibodies without producing susceptibility in the patient to infections, these drugs opened a new era in organ replacement. Transplants became world headlines on 3 December 1967 when Christiaan Barnard at the Groote Schuur Hospi tal, Cape Town, sewed a heart from a 24-year-old woman, who had died in a motor accident, into 54-year old Louis Washkansky. A second patient, Philip Blaiberg, operated on in January 1968, sur vived for 594 days.

Buy sporanox visa. The Best Anti-Cancer Foods.